A story through the centuries

With roots dating back thousands of years, Rougham Estate is proud of its rich historic legacy.

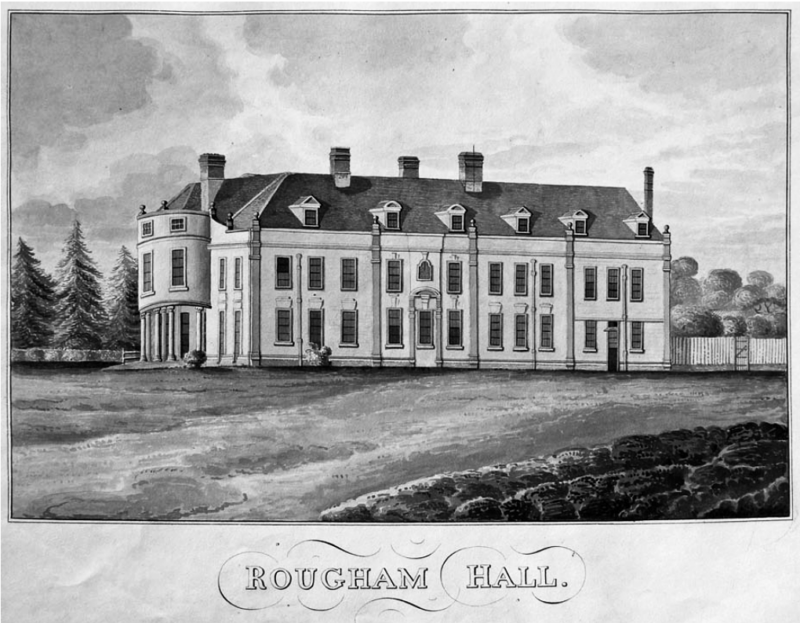

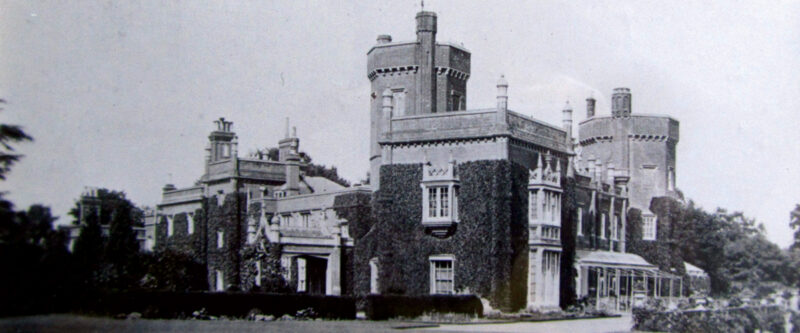

Nestled in Suffolk’s beautiful countryside, just a few miles from Bury St Edmunds, this beautiful estate has been a symbol of elegance and cultural significance for generations. With a history spanning over 2000 years, it has witnessed the changing epochs and preserves a crucial part of the region’s cultural legacy.

The Estate’s narrative weaves tales of enduring charm into the very fabric of Suffolk’s history with each era having left an indelible mark, from the Romans and Saxons to World War II and the bombing of Rougham Hall. Today it stands as a living testament to the region’s heritage, offering a glimpse into its storied past.

History Timeline

Find out more

Please Note

Rougham Hall is a ruin and is NOT open to the public. Anyone found trespassing at the hall site will have their details taken and be required to leave immediately.

The only way to visit the Hall is by attending one of the Guided Walks to the Hall.

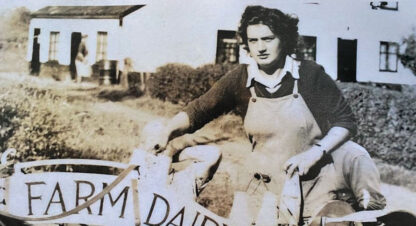

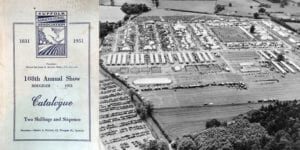

Gallery

The Rougham Post

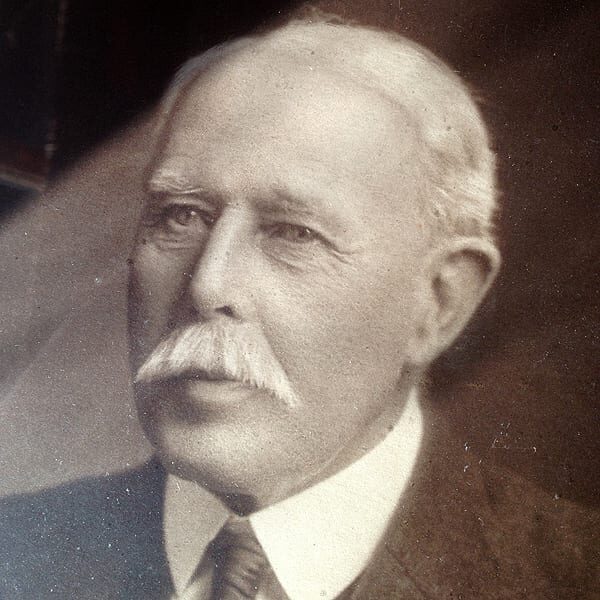

Remembering Rougham Estate from the past